The 4 Founder Communication Styles (And Their Blind Spots)

Why clarity fails when founders feel threatened

After a short pause, Founders’ Psyche is back. Starting the year with a piece on one of the most common founder failure modes: communication under pressure.

The conversation wasn’t supposed to turn into a conflict.

One founder believed they were being clear and direct.

The other walked away feeling dismissed.

A routine product discussion became tense. A Slack message created silence. An investor call ended politely and then never resumed.

Nothing objectively offensive was said. No one raised their voice. The intent on both sides was reasonable.

And yet alignment broke.

This is the quiet pattern inside startups. Communication fails not because founders lack intelligence or goodwill, but because they default to different ways of speaking under pressure.

Each founder believes they are being reasonable. Each assumes the other “should get it.”

They don’t.

Most breakdowns aren’t about the message itself. They’re about the communication style carrying it and the blind spots that come with it.

That’s what this blog explores.

Index

Why founder conversations break down even when intent is good

How psychology explains communication failures under pressure

The four communication styles most founders default to

The blind spots each style creates during conflict

Where different styles clash inside startups

A practical framework to handle hard conversations

Simple scripts founders can use immediately

How to prevent recurring misalignment as the company scales

Why Difficult Founder Conversations Go Wrong

Communication breakdowns aren’t character flaws. They’re predictable psychological responses to threat. When a cofounder critique lands wrong, your brain doesn’t distinguish between a sharp email and a physical danger. The amygdala floods your system with stress hormones, hijacking rational thought. This is what psychologist Daniel Goleman calls an “amygdala hijack,” the moment fight-or-flight takes over and you can’t think straight. Your heart rate spikes, you snap back or shut down entirely, and any hope of productive dialogue evaporates.

Add ego depletion to the mix. After twelve hours of decisions and firefighting, your self-control reserves are empty. Research from psychologist Roy Baumeister shows willpower is finite. By evening, a founder who’s usually diplomatic becomes brusque or withdrawn, not because they’ve changed, but because they’re mentally exhausted. In this state, small disagreements escalate fast.

Startups amplify these dynamics. Speed, ambiguity, existential stakes. One analysis found 65% of high-potential startups fail due to interpersonal tensions within the founding team. Under this pressure, founders start misreading intent. Silence becomes disengagement. Urgency becomes aggression. Psychologist John Gottman’s research shows that defensiveness, the instinct to deflect blame when criticized, blocks resolution and calcifies conflict over time. What starts as a style mismatch hardens into “we just can’t communicate.”

The Four Founder Communication Styles

Founders don’t have one communication mode. They have a default style that intensifies when pressure mounts. These styles aren’t personality types or diagnoses. They’re behavioral tendencies rooted in frameworks like the Social Style Model developed by David Merrill and Roger Reid, which maps communication along two axes: assertiveness and emotional responsiveness.

Understanding these patterns helps you recognize what’s happening in real time. No style is superior. Each has strengths that serve founders well in certain contexts and blind spots that sabotage them in others. The key is noticing when your default approach stops working and learning to translate across styles.

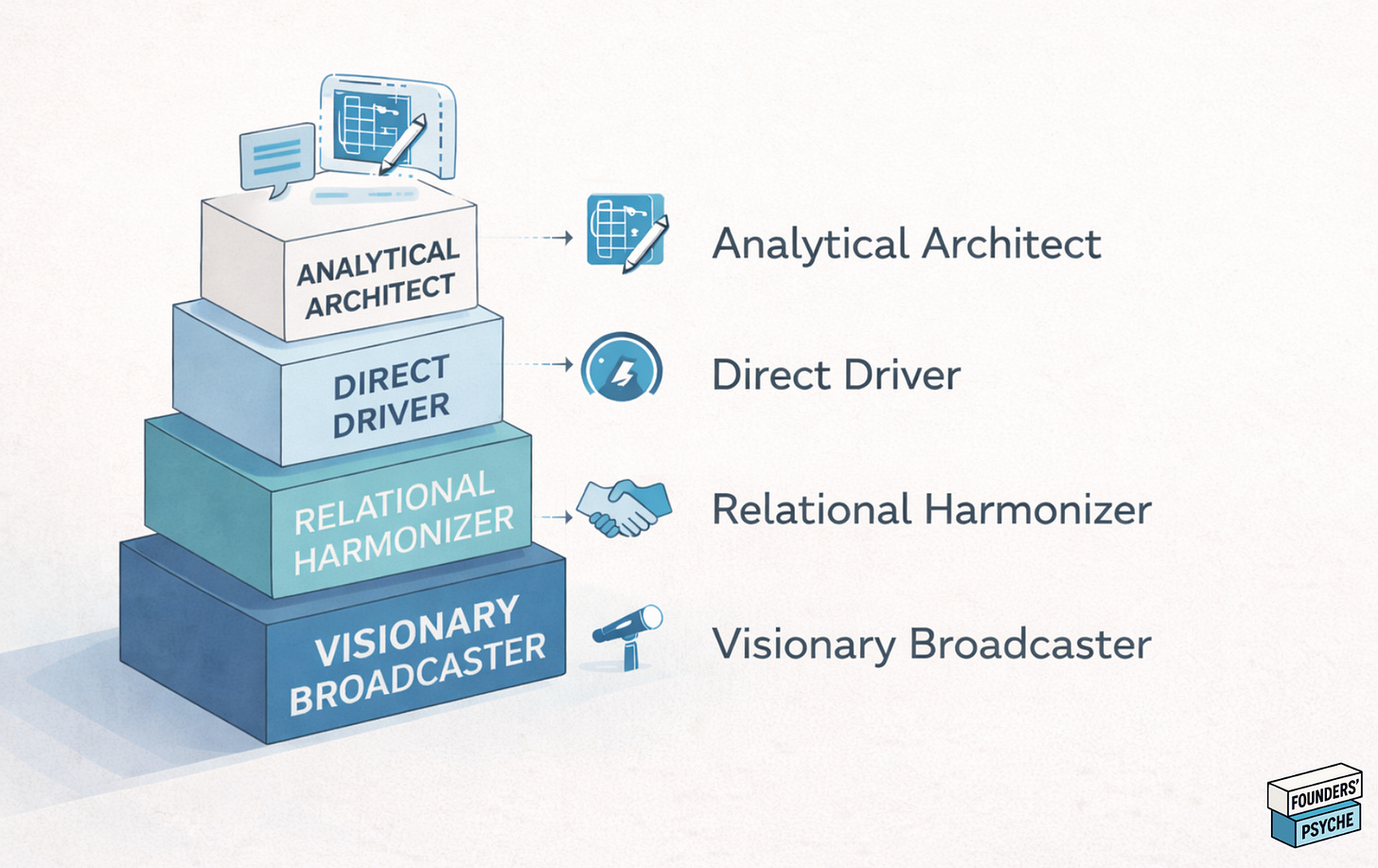

The four styles are:

The Analytical Architect, who leads with logic and precision.

The Direct Driver, who prioritizes speed and decisiveness.

The Relational Harmonizer, who values trust and team cohesion.

The Visionary Broadcaster, who paints big pictures and rallies around possibility.

Each style works beautifully until it collides with a cofounder operating from a completely different script.

The Analytical Architect

Architects process through data. They want the full picture before committing, and they communicate in layers of detail, caveats, contingencies. Their questions aren’t skepticism; they’re due diligence. In strategy discussions, an Architect will build financial models, map edge cases, and pressure-test assumptions until they’re confident the plan holds.

Strengths: Architects catch problems early. They reduce risk by spotting gaps others miss. In fundraising, they produce investor decks that answer every question before it’s asked. They’re credible, thorough, unshakeable under scrutiny. When a VC digs into unit economics, an Architect cofounder is gold.

Blind spots: Architects can suffocate momentum. Their need for completeness reads as hesitation to faster-moving cofounders. When an Architect says “let me think about that,” a Driver hears “no.” Their communication style, loaded with qualifiers and conditionals, can feel evasive or unconfident. Investors sometimes misread this carefulness as doubt about the vision itself.

Example: During a fundraising sprint, an Architect cofounder insists on refining the financial model one more time before sending it to a lead investor. To them, it’s about accuracy. To their cofounder, it feels like stalling when speed is everything. The delay costs them momentum, and the investor moves on. Neither intended sabotage, but the style mismatch created friction at the worst possible moment.

The Direct Driver

Drivers cut to the decision. They communicate in declaratives: “Here’s what we’re doing.” They value efficiency over nuance and see long explanations as wasted time. In their mind, clarity is kindness. When strategy needs deciding, a Driver will synthesize options, pick one, and move.

Strengths: Drivers create velocity. They unblock teams, force decisions, and prevent analysis paralysis. In fundraising, they’re compelling. They own the room, radiate confidence, and give investors the conviction that this team will execute. When a startup is stuck, a Driver cofounder breaks the logjam.

Blind spots: Drivers can bulldoze. Their bluntness lands as aggression, especially with cofounders who process differently. When a Driver says “this isn’t working, we’re switching,” others hear “your work was garbage.” They underinvest in explanation, assuming everyone sees what they see. This creates resentment. Team members feel unheard, steamrolled, reduced to executors of someone else’s plan.

Example: A Driver cofounder decides mid-quarter to pivot the go-to-market strategy and announces it in a Slack message. The rationale is clear to them, but the team feels blindsided. An Architect cofounder needed to understand why. A Harmonizer needed to process how it affects the team. The Driver thought they were being decisive. Everyone else felt disrespected. Within days, trust eroded.

The Relational Harmonizer

Harmonizers lead with empathy. They read the room, prioritize morale, and ensure everyone feels included before moving forward. Their communication is warm, collaborative, often framed as questions rather than directives. In strategic conversations, a Harmonizer checks in: “How does everyone feel about this direction?”

Strengths: Harmonizers build trust. They create psychological safety, which is essential for honest feedback and creative problem-solving. In team settings, they’re the glue. They spot when someone’s struggling and address it before it becomes a crisis. With investors, they’re likable and build rapport easily. They make rooms feel human, not transactional.

Blind spots: Harmonizers avoid conflict. Their desire to preserve harmony means they don’t surface disagreements until they’re too big to ignore. When they sense tension, they soften their message or withdraw, which can feel passive-aggressive to Drivers. In high-stakes moments like fundraising, their carefulness can read as uncertainty. Investors may wonder if they have the edge to make hard calls.

Example: A Harmonizer cofounder privately disagrees with the fundraising valuation but doesn’t speak up because the other founder feels strongly about it. Weeks later, in a pitch, an investor challenges the number. The Harmonizer’s hesitation in defending it signals doubt, and the deal momentum stalls. They weren’t uncertain about the business, but their conflict avoidance created ambiguity at the worst moment.

The Visionary Broadcaster

Broadcasters think in narratives. They communicate through stories, metaphors, big swings. They’re energized by possibility and inspire others by painting a future so vivid it feels inevitable. In strategy conversations, they zoom out: “Imagine if we owned this entire category.”

Strengths: Broadcasters rally teams and investors around a mission. They’re magnetic in rooms, turning skeptics into believers. In fundraising, they own the vision section of the pitch. They make people feel like they’re part of something historic. Broadcasters give startups their emotional center, the reason anyone cares beyond the spreadsheet.

Blind spots: Broadcasters skip the details. Their big-picture communication can feel unmoored from reality to Architects or Drivers who need a plan. When a Broadcaster says “we’ll figure it out,” others hear recklessness. They can over-promise, leaving the team to manage expectations or clean up commitments that weren’t fully thought through. In execution-heavy moments, Broadcasters can seem detached or impractical.

Example: In a fundraising meeting, a Broadcaster cofounder paints an audacious vision that excites the room. But when the investor asks about go-to-market mechanics, the Broadcaster pivots back to vision. The Architect cofounder has to step in with specifics, which creates a subtle dynamic where the investor wonders if the Broadcaster is all sizzle. The vision wasn’t wrong, but without grounding, it lost credibility.

Where Styles Clash

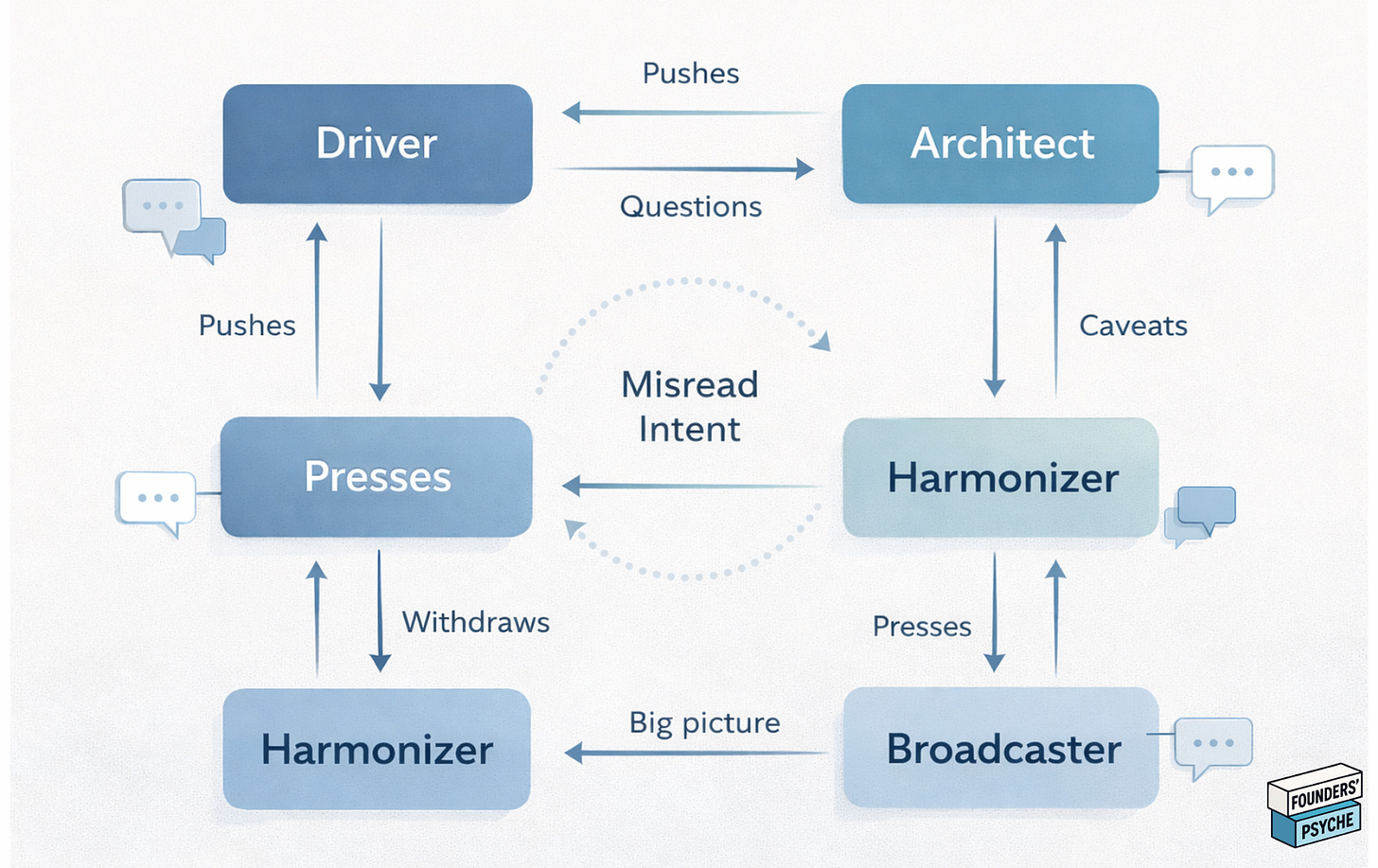

Most cofounder conflict isn’t personal. It’s two styles colliding in ways that each side misreads as intentional harm. An Architect’s thoroughness frustrates a Driver’s urgency. A Harmonizer’s indirectness looks like avoidance to a Direct Driver, while the Driver’s bluntness feels like cruelty to the Harmonizer. A Broadcaster’s big-picture energy reads as hand-waving to an Architect who needs precision, and the Architect’s caveats feel like wet blankets to the Broadcaster.

These clashes escalate predictably. When an Architect asks clarifying questions, a Driver interprets it as resistance and pushes harder. The Architect, feeling steamrolled, digs in or shuts down. Meanwhile, a Harmonizer trying to smooth things over gets dismissed as conflict-averse by the Driver, who sees their diplomacy as weakness. The Harmonizer retreats, which the Driver reads as disengagement. Each side assumes bad intent when the real issue is incompatible scripts running in parallel.

Psychologist Matthew Jones describes this as the “pursue-withdraw” dynamic: one person escalates to resolve the tension, the other pulls back to avoid it, and the cycle feeds itself. The Driver keeps pushing. The Harmonizer keeps withdrawing. No one hears each other. Similarly, when a Visionary Broadcaster gets excited about a new direction, the Architect cofounder raises ten concerns. The Broadcaster feels deflated, the Architect feels ignored, and both leave thinking the other doesn’t respect their contribution.

The tragedy is that these conflicts often happen during high-stakes moments like fundraising or pivots, when alignment matters most. And because founders attribute behavior to character instead of context, they personalize it. “She’s controlling.” “He’s checked out.” Research on the fundamental attribution error shows we judge others by impact while judging ourselves by intent.

We rarely stop to ask: what if this is just a style mismatch?

A Simple Framework for Hard Conversations

The fix is not better wording. It is better structure.

Most founder conversations break down because three things drift out of alignment: what you intend, the signal you send, and how the other person interprets it. When these are misaligned, even well meant conversations create friction.

A useful way to handle hard conversations is to make these three elements explicit instead of assuming they are understood.

Step 1: Make Your Intent Explicit

Start by naming your intent out loud.

Before raising the issue itself, say what you are trying to achieve. For example, “I am not criticizing the deck. I want to make sure we are ready for tough investor questions.” This small step dramatically reduces defensiveness because it removes ambiguity about motive.

When intent is left unsaid, the other person fills in the gap. Under pressure, they usually assume the worst. Clarifying intent first prevents the conversation from starting on the wrong emotional footing.

Step 2: Check the Signal You Are Sending

Next, examine how your message is being delivered.

Tone, timing, and medium matter as much as content. A late night Slack message about problems with strategy lands very differently from a calm, scheduled conversation framed as working through ideas together.

This is where communication styles matter. A fast, direct message from a decisive founder can feel harsh to a more relationship oriented cofounder. A broad, visionary message can feel vague or ungrounded to someone who prefers precision.

Before speaking, ask yourself how this signal will land given the other person’s style, not just your own.

Step 3: Invite Interpretation

After delivering your message, explicitly check how it was received.

Simple questions work. “How does that sound to you?” or “What did you hear me say?” This step surfaces misalignment in real time. If your cofounder heard criticism when you intended collaboration, you can correct course immediately instead of letting resentment quietly build.

This draws on a well established conflict resolution technique often called mirroring. One person reflects back what they heard, the other confirms or clarifies, and only then does the conversation move forward. It forces both sides to listen rather than prepare counterarguments.

Step 4: Adapt Delivery Without Losing Substance

Finally, adjust how you communicate based on the other person’s style.

If your cofounder values precision, lead with data and give them space to process. If they value speed and decisiveness, get to the point quickly. If they are relationship focused, acknowledge the human context before diving into the issue. If they are vision driven, connect the discussion to the larger mission.

This is not manipulation. It is translation. You are not changing what you believe. You are changing how you deliver it so it can actually be heard.

This framework works because it externalizes the problem. Instead of framing the issue as “you are being defensive,” the focus shifts to “our intent, signals, and interpretations are misaligned.” What felt like a personal conflict becomes a shared communication problem that both founders can solve together.

Scripts Founders Can Use Immediately

Hard conversations feel difficult not because founders lack empathy or clarity, but because pressure pushes everyone into their default style. The goal of these scripts is not to sound polished. It is to reduce defensiveness by making intent clear, respecting the other person’s style, and keeping the conversation collaborative.

Giving critical feedback to a Driver

“I want us to move fast, and I am aligned with the direction. I need five minutes to flag two risks I am seeing so we do not get blindsided later. Can we talk through them now?”

This works because it honors urgency while asserting the need to be heard. It signals alignment first, then introduces friction in a contained way.

Pushing back on an investor as an Architect

“That is a fair question. Here is what the data shows.”

Present the numbers.

“Based on this, we are confident in the direction. I would also like to understand if you are seeing something we are missing.”

This keeps the conversation grounded in evidence while staying open. It avoids defensiveness by framing disagreement as joint sense making.

Aligning with a Harmonizer cofounder on a tough call

“I know this conversation is uncomfortable, and I value how much you care about the team. I need us to address this directly because avoiding it will hurt them more in the long run. Can we work through it together?”

This acknowledges emotional reality first, then explains why directness is necessary. It protects the relationship while moving the issue forward.

Setting boundaries with a Broadcaster cofounder

“I love the vision and I am excited about where we are headed. Right now I need us to get concrete on the next three months so the team knows what to execute. Can we timebox the big picture and then drill into tactics?”

This validates energy and ambition while redirecting attention to execution.

These scripts work because they are not about clever wording. They name intent, adapt to the other person’s style, and invite collaboration instead of combat. They turn difficult conversations from personal standoffs into shared problem solving.

Prevention: Building a Culture of Clean Communication

The strongest cofounder relationships do not avoid conflict. They surface it early, handle it explicitly, and resolve it without emotional residue. That only happens when teams build habits that catch misalignment before it hardens into resentment.

Start by creating written context for important decisions. A short memo before a strategy discussion gives more analytical founders time to process and reduces the risk of fast moving voices dominating the room. It also keeps conversations anchored in substance rather than reactions. Clear written context levels the field across different communication styles.

Next, establish explicit decision rights. Be clear about who owns product calls, hiring decisions, or the fundraising narrative. When ownership is ambiguous, disagreements quickly turn personal. When ownership is clear, conflict stays focused on the decision itself rather than on control or territory.

Use asynchronous communication to reduce emotional overload. Not every issue needs to be resolved in a live meeting. A thoughtful message, document, or short Loom video allows people to process without the pressure of immediate response. This is especially helpful for founders who need time to reflect before reacting.

Set expectations before entering high pressure phases. Ahead of a fundraising sprint or launch, say something like, “I am going to be more direct than usual because we are moving fast. If something lands sharply, it is urgency, not frustration with you.” Naming this upfront prevents misinterpretation when stress is highest.

Finally, debrief not just on outcomes but on communication. After a difficult decision or tense exchange, ask, “How did that conversation land for you?” or “Did I communicate clearly, or did something feel off?” This normalizes talking about how you communicate, which is the only way teams improve it over time.

Founders who build these habits create cultures where tension is addressed cleanly. People speak directly, resolve issues early, and move forward without carrying hidden resentment. That is not therapy. It is operational hygiene.

P.S. I experimented with a short explainer video in the last post.

If you watched it, I’d love to know: did it help clarify the ideas, or did you prefer the text-only format?

A quick reply to this email is more than enough.

Key Takeaways

Founders don’t fail at communication. They default to styles that work in some contexts and backfire in others. Recognizing your style and your cofounder’s is the first step to reducing friction.

Every style has predictable blind spots. Architects overanalyze. Drivers bulldoze. Harmonizers avoid conflict. Broadcasters skip details. None of these are fatal, but all need managing.

Most cofounder conflict is style mismatch, not bad intent. When you assume the worst, you personalize what’s actually a behavioral pattern intensified by pressure.

Frameworks reduce emotional noise. Intent, signal, interpretation. Name what you’re trying to do, check how it’s landing, and adjust in real time.

Awareness plus translation beats better wording every time. The goal isn’t to fix your cofounder. It’s to communicate in a way they can actually hear.

Best,

Ashish